The Taste Trap: Unpacking The Diminishing Returns Of Good Taste

In a world constantly pushing us towards refinement, towards an ever-more curated existence, the pursuit of good taste often feels like an undeniable virtue. We aspire to sophisticated palates, impeccably designed homes, and wardrobes that speak volumes without uttering a word. From the perfectly brewed artisanal coffee to the obscure, independent film, we are taught that cultivating a refined aesthetic sense is a hallmark of a life well-lived. Yet, what if this relentless quest for the exquisite comes with an invisible, often unacknowledged cost? What if, beyond a certain point, we encounter the diminishing returns of having good taste, where the effort, expense, and emotional toll begin to outweigh the actual pleasure and benefit derived?

This article delves into that intriguing paradox, exploring the point at which our cultivated discernment transitions from an asset to a liability. We'll examine how the initial joys and advantages of developing good taste can gradually erode, leading to financial strain, social isolation, and even a profound sense of dissatisfaction. It’s a journey from appreciation to obsession, from enjoyment to burden, and ultimately, a call to re-evaluate what truly enriches our lives beyond the superficial sheen of perfection. Prepare to question whether your refined sensibilities are truly serving you, or if they’ve subtly trapped you in a gilded cage of escalating expectations.

Table of Contents

- The Allure of Refined Palates: What Defines "Good Taste"?

- The Initial Ascent: Where Good Taste Pays Dividends

- Understanding "Diminishing Returns" in the Context of Taste

- The Financial Drain: When Taste Becomes a Costly Obsession

- The Social Cost: Isolation in the Ivory Tower of Taste

- The Psychological Burden: Perfectionism and Dissatisfaction

- Breaking Free: Reclaiming Joy Beyond the Pursuit of Perfection

- Finding Your "Enough": Embracing Practicality and Personal Joy

The Allure of Refined Palates: What Defines "Good Taste"?

Before we dissect the concept of the diminishing returns of having good taste, it's crucial to establish what we mean by "good taste." It's not merely about adhering to current trends or possessing expensive items. True good taste often implies a deep understanding of aesthetics, quality, craftsmanship, and cultural context. It's the ability to discern beauty, functionality, and authenticity, whether in a piece of furniture, a musical composition, a culinary dish, or a fashion ensemble.

A person with good taste might appreciate the subtle notes in a complex wine, recognize the historical significance of an architectural style, or understand the nuanced interplay of colors and textures in an outfit. It's a cultivated sensitivity, often developed through exposure, learning, and critical observation. This discernment can manifest in various aspects of life: from interior design and art appreciation to food and beverage choices, literature, music, and even the way one conducts themselves socially. It’s about a certain level of sophistication and an eye for detail that transcends mere superficiality.

Initially, this cultivation of taste is overwhelmingly positive. It enriches life, opens up new avenues of enjoyment, and often enhances one's social standing. It allows for deeper appreciation of the world around us and can be a source of immense personal satisfaction. However, like many good things, the pursuit of taste can become a double-edged sword when taken to its extreme, leading us directly to the point where its benefits begin to diminish.

The Initial Ascent: Where Good Taste Pays Dividends

In its nascent stages, developing good taste undeniably yields significant dividends. It’s an investment that pays off in numerous ways, both tangible and intangible. This is the phase where the returns are high, and the benefits are clear, making the initial journey into refinement incredibly rewarding.

Social Capital and First Impressions

One of the most immediate benefits of cultivating good taste is the social capital it accrues. A well-dressed individual, a tastefully decorated home, or a discerning conversationalist often makes a stronger, more positive first impression. In professional settings, a polished appearance and an understanding of cultural nuances can open doors and build trust. Socially, sharing a refined palate for food, wine, or art can forge deeper connections and facilitate entry into certain circles. People are often drawn to those who exude an air of sophistication and appreciation for quality, perceiving them as more knowledgeable, successful, or simply more interesting. This initial phase of taste development is about learning the ropes, understanding the basics of quality, and making choices that generally elevate one's presentation and interactions.

Enhanced Personal Enjoyment

Beyond social benefits, good taste profoundly enhances personal enjoyment. Imagine moving from a generic, mass-produced coffee to a meticulously roasted single-origin brew; the difference in sensory experience is immense. Discovering the comfort of high-quality fabrics, the ergonomic design of well-crafted furniture, or the emotional resonance of a truly masterful piece of music enriches daily life. This heightened sensitivity allows for a deeper, more nuanced appreciation of experiences that might otherwise pass unnoticed. Life becomes more vibrant, more textured, and more pleasurable. The initial investment in learning to discern quality and beauty pays off in a consistently elevated quality of life, transforming mundane moments into delightful discoveries. This is where the positive returns are most evident, making the journey feel worthwhile and beneficial.

Understanding "Diminishing Returns" in the Context of Taste

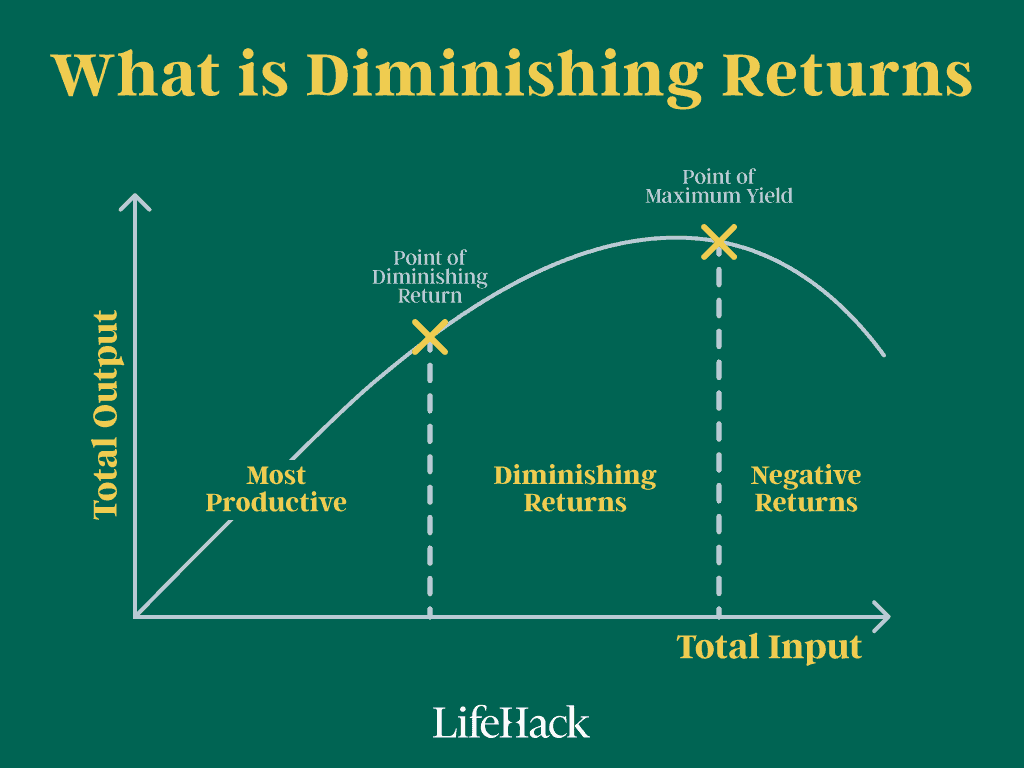

To fully grasp the core concept of the diminishing returns of having good taste, we must first understand what "diminishing returns" truly means. In economics, it refers to a point where the addition of more of one factor of production, while keeping other factors constant, eventually yields smaller and smaller increases in output. Put simply, you get less bang for your buck.

The meaning of diminish is to make less or cause to appear less. When we talk about how to use diminish in a sentence, we might say, "His diminishing respect for her became apparent with each dismissive comment." In the context of taste, the "returns" are the benefits, satisfaction, or advantages gained from cultivating and applying that taste. The present participle of diminish, "diminishing," perfectly describes the gradual reduction in these benefits. It means to reduce or be reduced in size or importance. So, the phrase "diminishing returns" indicates that the positive impact or satisfaction you gain from further refinement starts to lessen significantly, even as the effort or cost continues to increase.

Initially, a small investment in learning about quality fabrics might yield a significant improvement in your wardrobe and comfort. The return is high. However, as you delve deeper, moving from well-made basics to haute couture, the incremental improvement in comfort or aesthetic pleasure might be minimal, while the cost escalates exponentially. This is where you find 108 different ways to say diminishing, along with antonyms, related words, and example sentences at thesaurus.com., all pointing to the idea of a decline in effectiveness or benefit relative to effort. The curve of benefit flattens, even as the curve of cost or effort continues to rise steeply. It's the point where the pursuit of taste becomes less about genuine enjoyment and more about an endless, often unfulfilling, chase.

The Financial Drain: When Taste Becomes a Costly Obsession

Perhaps the most tangible manifestation of the diminishing returns of having good taste is its impact on one's finances. What starts as a healthy appreciation for quality can quickly spiral into an insatiable appetite for luxury, rarity, and exclusivity, leading to significant financial strain.

The Pursuit of Rarity and Exclusivity

Once you've cultivated a discerning eye, mass-produced items often lose their appeal. Your taste evolves, demanding something unique, handcrafted, or from a limited edition. This is where the cost curve begins its steep ascent. A perfectly good, comfortable sofa from a reputable brand might suffice for most, but someone with an advanced sense of taste might crave a bespoke piece from a renowned designer, costing ten or even hundred times more. The incremental increase in comfort or aesthetic pleasure might be negligible, but the price difference is astronomical. The same applies to fashion: moving from high-quality ready-to-wear to couture means paying for the artistry and exclusivity, not necessarily a proportional increase in wearability or fundamental beauty. The joy of acquisition becomes tied to scarcity and price tag, rather than intrinsic value. This constant chase for the "next big thing" or the "unobtainable" item means you're often paying a premium not for superior utility or beauty, but for the mere fact that few others can have it.

Maintenance and Lifestyle Inflation

Beyond the initial purchase, refined taste often necessitates a higher cost of living. Owning delicate, high-end clothing requires specialized dry cleaning. Fine art needs climate-controlled environments and insurance. Gourmet ingredients for cooking demand more expensive grocery bills. A home filled with designer pieces might require professional cleaning and meticulous upkeep. This phenomenon, known as lifestyle inflation, means that as your income grows (or even if it doesn't), your expenses grow to match your increasingly refined tastes. What was once a luxury becomes a perceived necessity, creating a treadmill of spending. The enjoyment derived from these items might not be proportional to the escalating costs. You're not just buying a product; you're buying into a lifestyle that has a much higher ongoing cost of maintenance and upkeep, subtly eroding your financial freedom and peace of mind. The financial returns on these escalating investments in taste rapidly diminish, leaving you with less disposable income for other life experiences or savings.

The Social Cost: Isolation in the Ivory Tower of Taste

While good taste can initially enhance social connections, pushing it to an extreme can paradoxically lead to social isolation. This is another significant facet of the diminishing returns of having good taste, often overlooked until it's too late.

When one's taste becomes exceedingly niche or refined, it can create a barrier between them and those who do not share the same level of discernment. Simple pleasures enjoyed by the majority might become unpalatable or even offensive. A casual dinner at a chain restaurant, a popular movie, or a widely appreciated piece of music might be dismissed with a sneer or a condescending remark. This can make it difficult to connect with people on common ground, as shared experiences become limited to a very select few who meet one's exacting standards.

Friendships can suffer when one person constantly critiques or elevates their own preferences above others. Imagine being invited to a friend's home only to silently (or not so silently) judge their furniture, their choice of wine, or their music playlist. This judgmental attitude, even if unspoken, can create distance and make others feel uncomfortable or inadequate. The pursuit of "perfect" experiences can also lead to a reluctance to engage in spontaneous, imperfect social outings, preferring to wait for the "right" kind of event or company.

Furthermore, the communities that cater to highly refined tastes are often small and exclusive. While this can foster deep connections within those specific niches, it can also limit one's exposure to diverse perspectives and broader social circles. The world becomes smaller, populated only by those who "get it," while everyone else is subtly (or overtly) deemed less sophisticated. This self-imposed segregation, born from an overzealous pursuit of taste, can lead to loneliness and a feeling of being misunderstood, as his diminishing respect for her taste in everyday things begins to erode the foundation of shared enjoyment.

The Psychological Burden: Perfectionism and Dissatisfaction

Beyond the financial and social implications, the relentless pursuit of good taste can exact a heavy psychological toll, leading to perfectionism, anxiety, and a pervasive sense of dissatisfaction. This is arguably the most insidious aspect of the diminishing returns of having good taste.

The Endless Pursuit of "Better"

Once you've trained your eye and palate to recognize the absolute best, everything else can start to feel subpar. A perfectly good meal becomes merely "acceptable," a comfortable chair "adequate," and a beautiful piece of art "nice, but not truly exceptional." This constant comparison to an ever-higher ideal can strip joy from everyday experiences. The bar for satisfaction is continually raised, making it harder and harder to feel content with what you have. This isn't just about consumer goods; it extends to experiences, relationships, and even self-perception. The mind becomes a relentless critic, always seeking flaws and imperfections, always striving for an elusive "better." This endless pursuit means that true contentment remains perpetually out of reach, as the goalpost of "good enough" constantly shifts further away. The joy derived from acquiring or experiencing something new quickly diminishes as the focus immediately shifts to the next, even more refined, object of desire.

This psychological burden manifests as anxiety about making the "right" choice, fear of being perceived as having "bad" taste, and a constant pressure to keep up with the latest trends or obscure knowledge within one's chosen niche. Social media exacerbates this, creating an illusion of effortless perfection that further fuels comparison and self-doubt. The pleasure of a simple, well-made item is replaced by the stress of needing the most exclusive, most expensive, or most obscure version. This relentless drive for perfection, ironically, leads to a state of perpetual dissatisfaction, where genuine enjoyment is overshadowed by an internal critic and the fear of falling short. The mental energy expended on maintaining this facade of impeccable taste far outweighs the fleeting moments of satisfaction it might provide, clearly illustrating the diminishing returns.

Breaking Free: Reclaiming Joy Beyond the Pursuit of Perfection

Recognizing the diminishing returns of having good taste is the first step towards liberation. It's about shifting perspective and reclaiming joy from a life that might have become overly dictated by external standards of refinement. Breaking free doesn't mean abandoning all appreciation for quality or beauty; rather, it means re-calibrating your relationship with it.

One crucial aspect of this liberation is embracing "good enough." Not everything needs to be the absolute best, the most exclusive, or the most expensive. There's immense freedom in finding satisfaction in things that are simply functional, comfortable, or aesthetically pleasing without being groundbreaking. This involves consciously lowering the bar for what constitutes "acceptable" or "enjoyable," allowing for a wider range of experiences and possessions to bring contentment. It's about letting go of the internal critic that constantly whispers, "But it could be better."

Another powerful strategy is to prioritize experiences over possessions. While a beautifully designed home or a designer outfit can bring pleasure, the memories created through travel, shared meals with loved ones, or engaging in hobbies often provide deeper, more lasting satisfaction. These experiences are less susceptible to the hedonic treadmill, as their value lies in the moment and the connection, rather than their intrinsic material worth. Shifting focus from accumulation to experience can dramatically reduce financial pressure and free up mental space.

Cultivating gratitude for what you already have is also paramount. Instead of constantly looking for the next upgrade or the next perfect item, take time to appreciate the beauty and utility of your current possessions. This practice can counteract the consumerist drive that often accompanies the relentless pursuit of taste. By consciously acknowledging and valuing what is already present, you can find contentment without needing to acquire more, thus breaking the cycle of diminishing returns.

Finding Your "Enough": Embracing Practicality and Personal Joy

Ultimately, the journey away from the perils of the diminishing returns of having good taste leads to a more balanced and fulfilling life. It's about defining your own "enough" and recognizing that true joy often resides not in external validation or endless acquisition, but in practicality, personal values, and genuine connection.

Embracing practicality means making choices based on utility, durability, and value, rather than solely on brand name or perceived prestige. It's understanding that a comfortable, well-made pair of shoes that lasts for years is often more valuable than a fleeting fashion statement. It's recognizing that a delicious home-cooked meal, prepared with love, can bring more satisfaction than an exorbitantly priced dish at a Michelin-starred restaurant. Practicality isn't about sacrificing quality entirely; it's about finding the sweet spot where quality meets common sense, where the returns are still high without the exponential increase in cost or effort.

Furthermore, prioritizing personal joy over societal expectations of taste is crucial. Your preferences are unique, and what brings you genuine happiness might not align with what is deemed "good taste" by a select few. Perhaps you find immense joy in collecting vintage toys, even if they don't fit a minimalist aesthetic. Or maybe you prefer simple, hearty comfort food over avant-garde cuisine. Embracing these personal joys, without judgment or comparison, allows for a more authentic and contented existence. It means listening to your own desires and needs, rather than being swayed by the opinions of others or the dictates of an ever-shifting aesthetic landscape.

This re-evaluation of taste allows for greater financial freedom, deeper and more diverse social connections, and a profound sense of psychological peace. It's about living a life that is rich in experiences and genuine satisfaction, rather than being perpetually caught in the trap of wanting more, needing better, and constantly chasing an elusive ideal. It's the ultimate act of self-care: choosing contentment over the endless, often exhausting, pursuit of perfection.

Conclusion

The journey from developing an appreciation for quality to becoming enslaved by the relentless pursuit of "perfect" taste is a subtle one, often imperceptible until its negative effects become undeniable. We've explored how the diminishing returns of having good taste can manifest as significant financial burdens, social isolation, and a pervasive sense of dissatisfaction, effectively turning a virtue into a vice. The initial benefits of discernment—enhanced enjoyment and social capital—eventually plateau, while the costs in terms of money, time, and mental well-being continue to escalate.

Understanding that the meaning of diminish is to make less or cause to appear less, and recognizing that the returns on our investment in taste can indeed diminish, is a powerful realization. It's a call to action to re-evaluate our priorities, to question whether our refined sensibilities are truly serving our happiness, or if they've become an unyielding master. By embracing "good enough," prioritizing experiences over possessions, and cultivating gratitude, we can break free from this gilded cage.

Ultimately, the goal isn't to abandon taste altogether, but to cultivate a balanced, healthy relationship with it. It's about finding your personal "enough," where practicality meets genuine joy, and where your choices are driven by authentic desires rather than external pressures. We invite you to reflect on your own relationship with taste. Are you truly enjoying your cultivated palate, or is it leading to a constant state of wanting more? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below, and consider exploring other articles on our site that delve into mindful consumption and living a more contented life.

The Diminishing Returns of Having Good Taste - The Atlantic

The Law of Diminishing Returns

What Are Diminishing Returns And How to Prevent Them - LifeHack